Herniated Disc

Herniated Disc: Definition

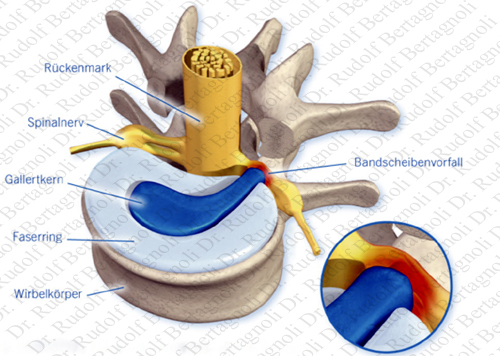

A herniated disc is a pathological condition in which a tear in the outer, fibrous ring (annulus fibrosus) of an intervertebral disc allows the soft, central portion (nucleus pulposus) to be extruded (herniated) to the outside of the disc. A herniated disc normally develops from a previously existing disc protrusion (sometimes called a contained herniated disc), a condition in which the outermost layers of the annulus fibrosis are still intact and the nucleus pulposus has not ruptured into the surrounding area. The nucleus pulposus is quite irritating to tissue outside of the disc and creates pain when it comes into contact with nerves. However, a true herniated disc can be called a prolapsed disc, when the annulus is ruptured and the nucleus pulposus has escaped.

In medicine and other technical fields it is very important to have one’s terminology in order. However, the general public also develops its own terminology, which should be discussed and bridged to the medical field. The popular term "slipped disc" is quite misleading, as an intervertebral disc, being tightly sandwiched between two vertebrae, cannot actually "slip," "slide," or even get "out of place." The disc is actually grown together with the adjacent vertebrae and can be squeezed, stretched, and twisted, all in small degrees. It can also be torn, ripped, herniated, and degenerated, but it cannot "slip."

“Pinched nerve” is also a misnomer, although the disc can put pressure on a nerve causing great pain.

Herniated Disc: Most Often Treated

A herniated disc most often occurs, when a person is in their thirties or forties, when the nucleus pulposus is still a gelatin-like substance. With age the nucleus pulposus changes (dessicated is what is most often printed on the MRI report) and the risk of herniation is greatly reduced. Unfortunately, osteoarthritis and disc degeneration will progress during these years.

The upper two cervical intervertebral spaces, the sacrum, and the coccyx have no discs and are therefore exempt from disc problems

.

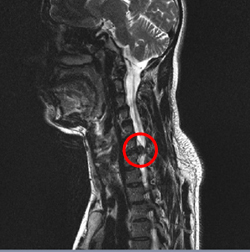

Herniated Disc: Cervical (neck)

A herniated disc in the neck occurs most often between the fifth and sixth or the sixth and seventh cervical vertebral bodies. Symptoms can affect the back of the skull, the neck, shoulder girdle, scapula, shoulder, arm, and hand. The nerves of the cervical plexus and brachial plexus can be affected. The cervical discs are affected 8% of the time.

Herniated Disc: Thoracic (chest)

A herniated disc in the chest is quite rare. Herniation of the uppermost thoracic discs can mimic cervical disc herniations, while herniation of the other discs can mimic lumbar herniations. Thoracic discs herniated only 1 - 2% of the time.

Herniated Disc: Lumbar (lower back)

A herniated disc in the lower back occurs most often between the fourth and fifth lumbar vertebral bodies or between the fifth and the sacrum. Symptoms can affect the lower back, buttocks, thigh, and may radiate into the foot and/or toe. The sciatic nerve is the most commonly affected nerve, causing symptoms of sciatica. The femoral nerve can also be affected. Lumbar disc herniation occurs 15 times more often than cervical (neck) disc herniation, and it is one of the most common causes of lower back pain

Herniated Disc: Causes

Causes of a disc of a herniated disc can include general wear and tear on the disc over time, repetitive movements and stress on the disc that occurs while twisting and lifting, spondylosis or other injuries.

Herniated Disc: Symptoms

Symptoms of a herniated disc can vary depending on the location of the herniation and the types of soft tissue that become involved. They can range from little or no pain if the disc is the only tissue injured to severe and unrelenting neck or back pain that will radiate into the regions served by an affected nerve root when it is irritated or impinged by the herniated material. Other symptoms may include sensory changes such as numbness, tingling, muscular weakness or paralysis, and affection of reflexes. Unlike a pulsating pain or pain that comes and goes, which can be caused by muscle spasm, pain from a herniated disc is usually continuous.

It is possible to have a herniated disc without any pain or noticeable symptoms, depending on its size and location. If the extruded nucleus pulposus material doesn't press on soft tissues or nerves, it may not cause any symptoms. It has been estimated that as many as 50% of the population have focal herniated discs in their cervical region that do not cause noticeable symptoms.

Typically, symptoms of a herniated disc are experienced only on one side of the body. If the prolapse is very large and presses on the spinal cord or the cauda equina in the lumbar region, affection of both sides of the body may occur, often with serious consequences.

Herniated Disc: Diagnosis

Diagnosis of a herniated disc is made by a practitioner based on the history, symptoms, and physical examination. At some point in the evaluation, tests may be performed to confirm or rule out other causes of symptoms such as spondylolisthesis, degeneration, tumors, metastases and space-occupying lesions as well as evaluate the efficacy of potential treatment options. These tests may include the following:

Herniated Disc: Treatment (Conservative)

The majority of herniated discs will heal themselves in about six weeks and do not require surgery. Your doctor may prescribe bed rest (usually for no more than two days), or advise you to maintain a low, painless activity level for a short period. If your doctor recommends physical therapy, this may include pelvic traction, gentle massage, ice and heat therapy, ultrasound, electrical muscle stimulation, and stretching exercises. Pain medications are often prescribed to alleviate the acute pain and allow the patient to begin exercising and stretching.

There are a variety of non-surgical care alternatives to treat the pain, including:

- Physical therapy

- Osteopathic/chiropractic manipulations

- Massage therapy

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

- Oral steroids (e.g. prednisone or methyprednisolone)

- Epidural (cortisone) injection

- Intravenous sedation, analgesia-assisted traction therapy (IVSAAT)

The presence of cauda equina syndrome (in which there is incontinence, weakness and genital numbness) is considered a medical emergency requiring immediate attention and possibly surgical decompression.

Herniated Disc: Treatment Surgical Options

If pain is severe and continuous, or if there are neurological deficits, surgery may be recommended. Surgical options include:

- Artificial Disc Replacement

- Discectomy

- Formainotomy

- Nucleoplasty

- Nucleotomy

Surgical goals include relief of nerve compression, allowing the nerve to recover, as well as the relief of associated back pain and restoration of normal function.

Herniated: Surgery Risks

All surgery carries risks from anesthesia, blood clots and infections. If complications from these risks arise, they most often can be successfully treated. The physical condition of the patient (such as obesity and diabites) can also add risk to surgery.

Herniated Disc: Surgery Long-Term Outlook

The appropriate surgical procedure properly executed will provide long term relief for the degenerated disc(s) treated. However, if the condition was allowed to continue too long and the nerves have become damaged, there may be some remaining pain or numbness or no improvement. Also, any degenerative process will likely continue, therefore problems in other areas of the spine may appear at a later time.

Herniated Disc